LooPIN - TestNet Summary and Main Net Upgrades

LooPIN's test net launched on April 9, 2024, and over 190 days have passed since. During this time, the protocol has undergone extensive testing. While its robustness has been confirmed, several potential improvements have been identified. This blog summarizes our test net report and highlights the changes implemented for the main testing phase.

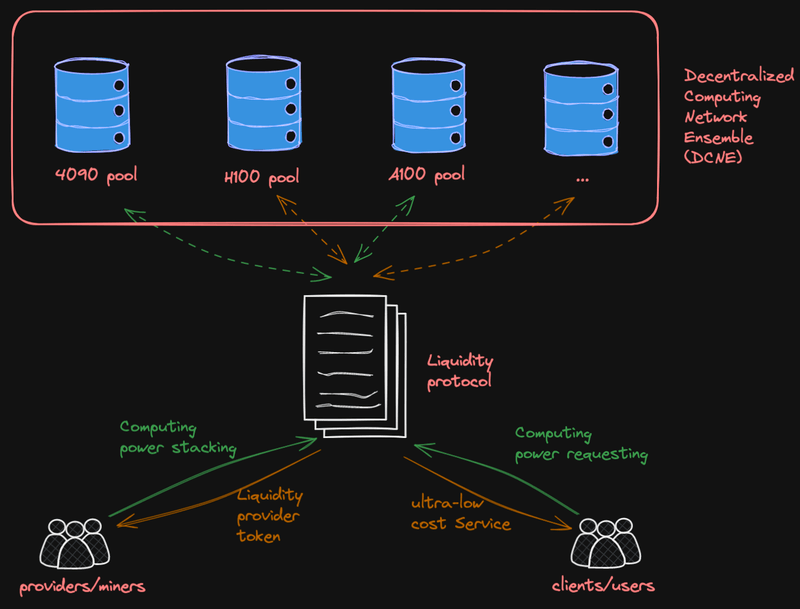

Liquidity Providers and Proof-of-Computing-Power-Staking (PoCPS)

At LooPIN, our goal is to provide a robust protocol that offers stable computing resources to users while ensuring long-term engagement from both users and liquidity providers. The stability of the computing resources supplied by liquidity providers is crucial to enhancing the usability of the protocol. We aim to create a system where users consistently rely on LooPIN, and liquidity providers are motivated to offer stable computing power. However, several issues emerged during our testnet phase:

- Stability of Computing Resources: The original Proof of Computing Power Stability (PoCPS) we proposed has proven insufficient for achieving enterprise-level stability. Some liquidity providers had GPUs that passed PoCPS verification, but when users purchased GPU hours, the machines failed to meet their performance requirements. New nodes lacked a proper test period during the testnet phase, leading to instability in resource availability.

- Liquidity Token Volatility: While this issue didn’t occur during the testnet phase, we anticipate that liquidity providers might sell large amounts of LooPIN tokens in the mainnet, prompting others to do the same. This could result in token instability and hinder the protocol's scalability.

- Data Privacy Concerns: AI researchers, one of our key user groups, expressed concerns about data safety. The original PoCPS algorithm did not include measures to protect user data privacy.

While the original PoCPS is a robust Proof of Work (PoW) algorithm designed to prevent several major attack vectors, it does not address the critical needs of stability, scalability, or privacy. To tackle these challenges while maintaining the PoW foundation of our protocol, we’ve extended the original PoCPS framework to include:

Where:

- PoT (Proof-of-Time) addresses time-based stability testing,

- PoL (Proof-of-Loyalty) focuses on liquidity management and control,

- PoP (Proof-of-Privacy) enhances privacy safeguards for user data, and

- PoW (Proof-of-Work) represents the original PoCPS proposed in our whitepaper.

This new structure aims to improve stability, scalability, and privacy while preserving the core elements of our protocol.

The PoT, PoL, PoP, and PoW can be defined as follows:

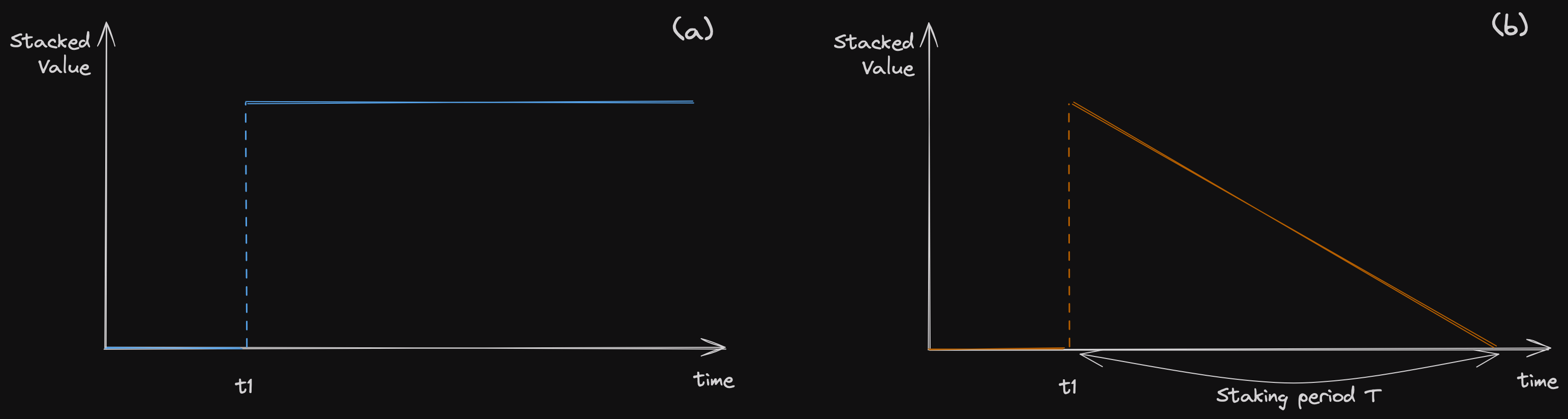

PoT (Proof-of-Time): The Proof-of-Time rewards are based on how long a node has been part of the protocol. The longer a node remains active, the greater the rewards it can earn, capped by the number of nodes in the network. The formula for PoT is:

Where

- is the time the node has been in the protocol,

- is the ramp-up period after which a node receives full rewards,

- determines the rewards for new nodes.

Currently,

- meaning that a newly added node can earn 10% of the total rewards until , and

- days in the main net phase.

PoL (Proof-of-Loyalty): The Proof-of-Loyalty is related to how much of the LooPIN token the node has sold. Nodes that sell more tokens show lower loyalty and thus receive lower rewards. The formula for PoL is:

Where

- is the current amount of LooPIN tokens held by the node,

- is the total amount of LooPIN tokens minted by the node over its lifespan,

- controls the reward reduction for nodes that have sold a significant portion of their tokens.

Currently .

PoP (Proof-of-Privacy): The Proof-of-Privacy rewards nodes based on how well they protect user data. Nodes that maintain higher privacy standards receive higher rewards. The formula for PoP is:

Where

- is the node's privacy level,

- is the benchmark privacy level,,

- determines the reward reduction for nodes with lower privacy standards.

Currently .

PoW (Proof-of-Work): The Proof-of-Work rewards are based on the performance of the node compared to similar GPUs in the network. Nodes with better performance receive higher rewards. The formula for PoW is:

Where

- is the performance level of the node,

- is the benchmark performance level,

- determines the reward reduction for underperforming nodes..

Currently

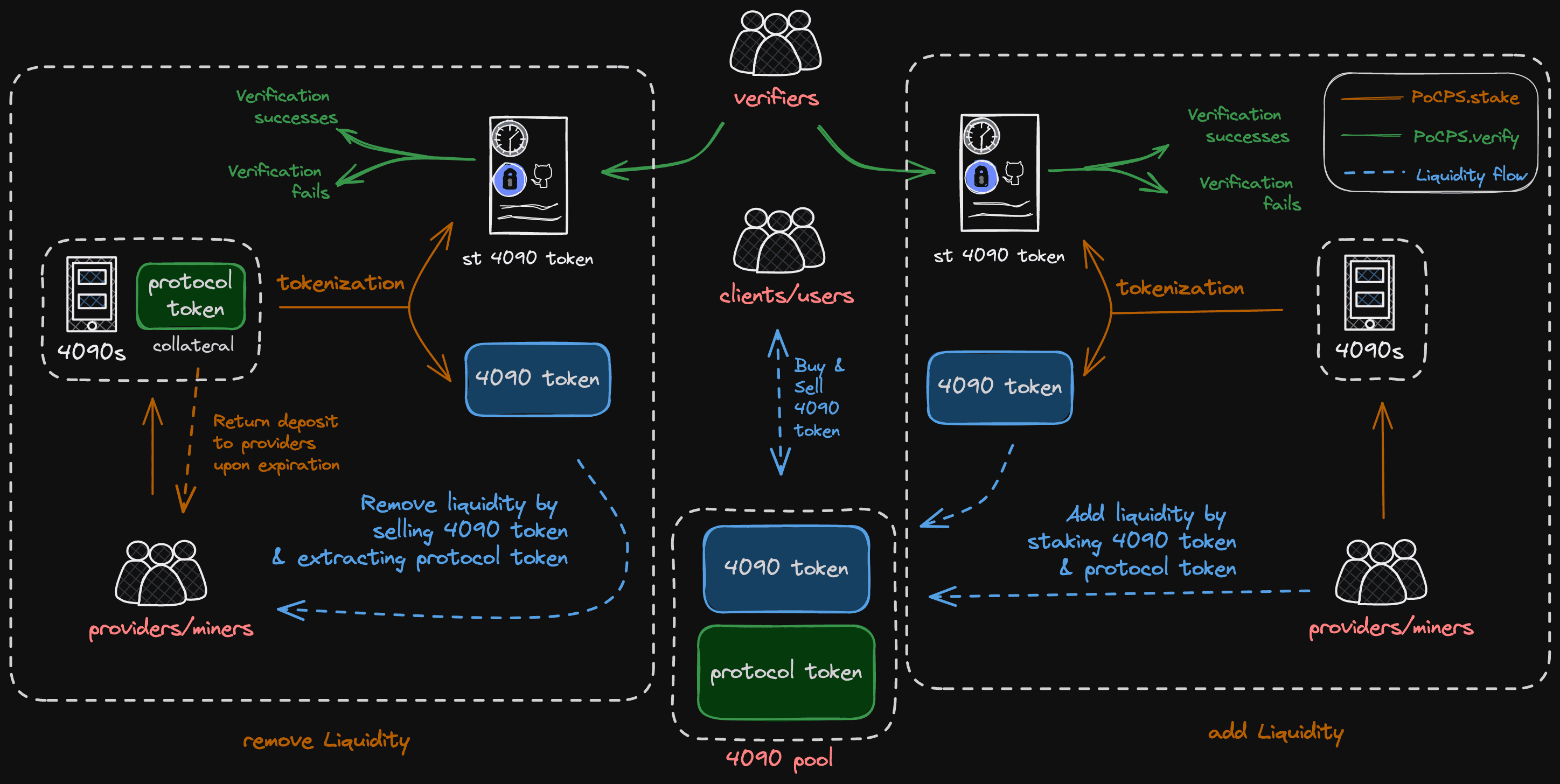

Liquidity of the Computing Power Pools

During our testnet phase, the protocol required liquidity providers to stake LooPIN tokens equivalent to 24 hours of computing power for each machine they added to the liquidity pool. The original rationale was that LooPIN tokens are limited, and staking a larger amount would be challenging. Additionally, token transfers between miners were uncommon, making it difficult for data centers to participate. As the testnet progressed, some issues became apparent:

- Due to the limited depth of the liquidity pool, computing power prices experienced significant fluctuations. For instance, the price of A100 GPUs swung from 1.3 to 0.9 in a single day, and this occurred frequently.

This volatility has been especially problematic for our users in universities and AI research labs, who have urged us to stabilize prices and make the protocol more user-friendly. To address these concerns, we've increased the staking requirement from 24 hours (one day) to 7 days (one week) for liquidity providers. With more staked computing hours and LooPIN tokens, the depth of the liquidity pools will increase, reducing price volatility to just 14% of what it was during the testnet phase. We can further increase the staking requirement, but we leave this for the next phase.

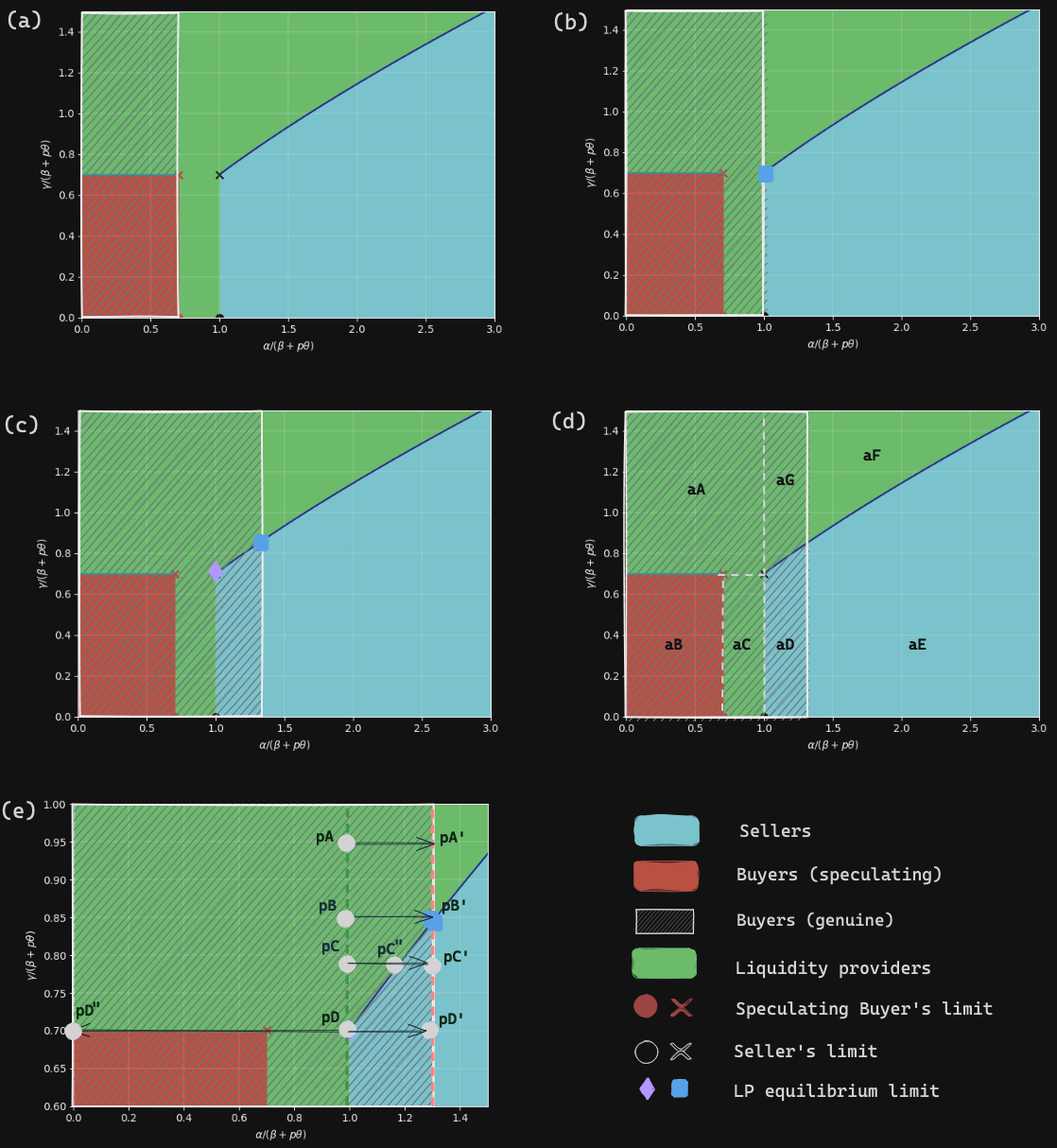

Speculative Resource Selling

During our testnet phase, the protocol allowed speculative sellers to offer their computing resources in hourly increments, with a minimum of 1 hour and a maximum of 24 hours. The intent behind this setup was to enhance liquidity, giving sellers as much flexibility as possible in selling their computing power. However, the testnet revealed several issues:

- For computing power sold in 1-hour increments, it was difficult for the protocol to match users before the time elapsed, leading to a high percentage of unused time.

- Most sellers were from data centers, and their demand to sell exceeded the 24-hour maximum.

Given that LooPIN aims to be a highly efficient protocol, reducing the percentage of unused time is essential. As a result, we've adjusted the selling resolution to 1 day, with a minimum selling period of 1 days (one day) and a maximum of 7 days (one week) in our main net phase. This also means that computing power sold to extract liquidity from the pool must maintain the machine's usability for a longer period.

Additionally, to further enhance network stability, we’re increasing the collateral amount from 1x to 100x the value of the sold GPU hours. This adjustment helps prevent malicious sellers from engaging in token price arbitrage.

Buyers

During our testnet phase, the protocol allowed buyers to purchase computing resources in hourly increments, with a minimum of 1 hour and a maximum of 24 hours. However, users in universities and AI research labs emphasized the importance of being able to extend the duration of their original purchase and to terminate instances early. In response, we have implemented these features in our mainnet phase, making the protocol more accessible and user-friendly.

Liquidity Pool

Based on feedback from startups and research labs, we're adding more enterprise GPUs for AI training. Since AI training requires extra RAM and TFlops, we'll include H100 (SXM or PCIe) and L40 (L40s) in our liquidity pool with staking rewards. We'll also bring in next-gen GPUs like the RTX 5090 for AI inference tasks in the near future. Additionally, we'll gradually retire older or less popular GPUs like the RTX 4080/3080, RTX 4070/3070, Tesla T4, and V100 based on usage and rental history.